Maui Nui (Maui, Moloka‘i, Lana‘i, Kaho‘olawe)

Maui Nui consists of four high islands--Maui, Lānaʻi, Molokaʻi, and Kahoʻolawe--and the small islet Molokini Crater. Each island has unique characteristics that affect their susceptibility to wildfires. The majority of wildfires across Maui Nui are caused by human error or arson, especially near developments, power line right of ways, and along roadsides.

Maui

Known as the “Valley Isle,” Maui is composed of two prominent mountains joined by a wide, flat central valley.

The western most volcano (also known as the West Maui Mountains) is Kahālāwai or "house of water." However, in recent times, most of this area is susceptible to recurring drought. This contributes to large swaths of dry vegetation at high risk for burning, which is especially apparent on former agricultural lands on the drier lee side. At the southern end of Kahālāwai lies the harbor town of Maʻalaea. This area has regular high winds and little rain, and the grassy slope above experiences frequent large fires.

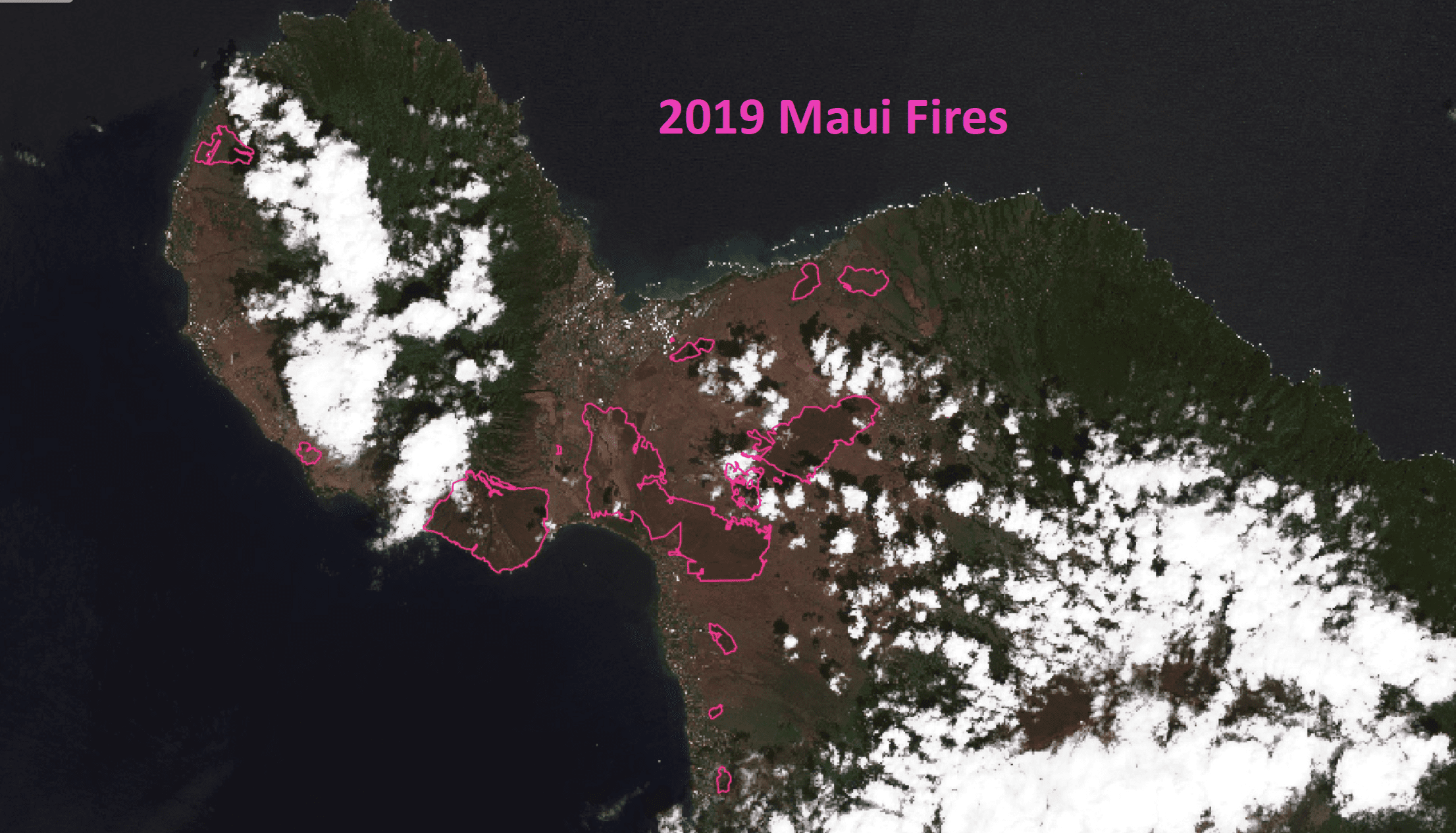

In the central valley, the four prominent streams known as Nā Wai ʻEhā once fed extensive loʻi kalo, or wetland taro patches. Sugarcane plantations were eventually even more extensive, and covered most of the central valley up until 2016, when the last sugarcane plantation in Hawaiʻi ceased operations. Just three years later more than 17,000 acres of that former agricultural land burned due to overgrowth of invasive grasses. >> READ MORE

East of the central valley, Haleakalā volcano has characteristic wet and rainy conditions on the northeastern (windward) side and dry leeward zones on the south shore. The higher elevation areas of Upcountry on the slopes of Haleakalā are more populated than on other islands. As a result, there are more ignitions and therefore fire risk, especially on the drought-prone, grassy leeward region from Kula to Kīhei. Another area with frequent ignitions and wildfires is Kahikinui. Both Kula and Kahikinui were once home to dryland forests, but they have been largely deforested at low to mid-elevations,now dominated by invasive species.

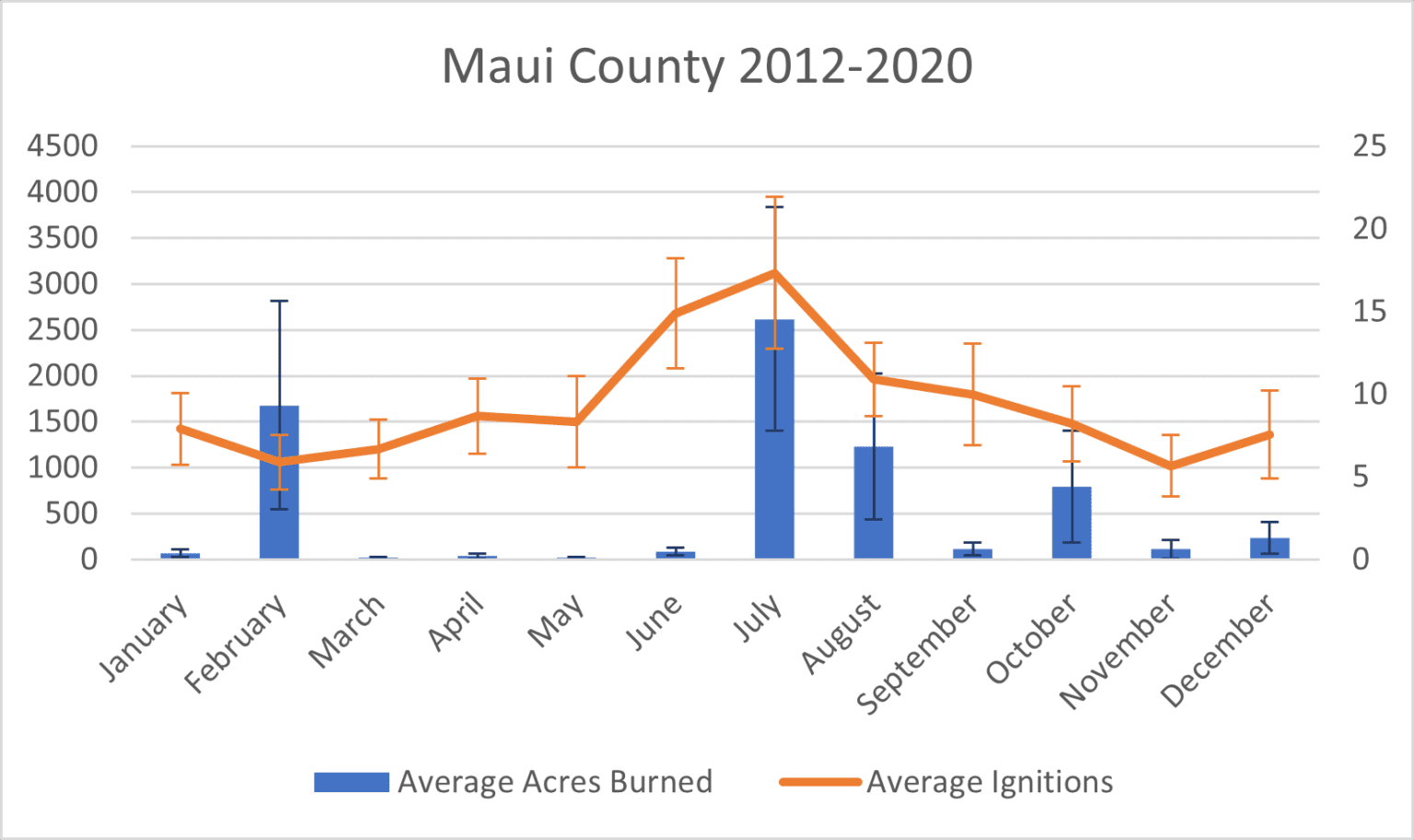

Seasonal variation in rainfall also affects both ignitions and area burned. Particularly wet periods over a rainy season can, counterintuitively, significantly elevate hazard levels. Increased precipitation may lead to a surplus of vegetation growth, becoming potential fuel during subsequent drier periods, thereby elevating the risk of large wildfires. Given the changing wind and rainfall patterns arising from climate change, this may lead to increased risk.

In recent years, severe storms such as hurricanes have emerged as potent catalysts for wildfires in the arid grasslands of contemporary Maui. This was most dramatically observed during the 2000+ acre fires that occurred during Hurricane Lane in 2018 and the tragic 2023 fires in Lāhainā and Kula. The high winds accompanying these storms initially deplete the land of moisture and humidity, creating conditions primed for potentially catastrophic wildfires. Subsequently, these winds not only cause the rapid spread of wildfires but also hinder firefighting efforts, making it a multifaceted challenge for disaster management.

Lānaʻi & Molokaʻi

Lānaʻi and Molokaʻi see fewer ignitions, but those that do occur are mostly near developments, power line right of ways, and along roadsides. Dry grass and shrublands dominate much of both of these islands. Once ignited, these species often act as uninterrupted ‘wicks’ that allow fires to spread from communities and roads (where ignition risk is highest) into areas that have contiguous fuels and more challenging access for firefighting efforts. >> READ MORE

Lānaʻi City in particular, presents a concerning fire risk due to its built history as an old, mostly wooden plantation town, now surrounded by old sugarcane fields. The risk lies not only in the potential loss of property but also the threat to lives and the surrounding natural environment. Proactive fire mitigation measures are essential to reduce the risk of Lānaʻi City facing a fire disaster akin to Lāhainā.

Molokaʻi has also experienced serious wildfires. For example, three wildfires between 1988 - 1998 burned more than 10,000 acres, or nearly 5% of the island. The after-fire impacts of soil loss and sedimentation on the longest fringing reef in the U.S. caused stress upon local subsistence fishing as a food source.

Kahoʻolawe

Although not permanently inhabited, Kahoʻolawe does see human activity as well as wildfires. A rotation of environmental and cultural restoration workers stay on the island, and have relevant facilities. Originally a forested island, it is now almost entirely hardpan with grass and shrublands, and is highly susceptible to drought. It was used for bombing practice by the US Military from 1941 to 1993 and many unexploded ordinances remain on the island. The presence of unexploded ordinance prevents most firefighting efforts once a fire is ignited, as was the case in the 2020 fire that burned over a third of the island, including restoration workers’ main storage facility. >> READ MORE

Recent Resources For Hawai‘i

Dr. Kim Burnett, Assistant Director of the University of Hawai`i Economic Research Organization presents some of her economic analysis of Hawaiian dry forest restoration as well as wildfire-related work in the aftermath of the August 2023 Maui fires.

Dr. Lisa Gollin is an applied anthropologist and social scientist who presented her findings from interviews she conducted as part of the project “Challenges to Rapid Wildfire Containment in Hawaii”.

Since the arrival of European and American settlers in the late 18th century, the cultural and economic landscape of Hawaiʻi has undergone rapid and profound transformations.