AMY, KAIMANA, AND MIKAELA CHECK OUT THE VIEW OF LOWER MAKAHA VALLEY

Took a trip to Makaha Valley with Amy Tsuneyoshi and Kaimana Wong from the Honolulu Board of Water Supply (HBWS) and Mikaela Bolling from the Waianae Mountain Watershed Partnership (WMWP) to check out two fire breaks they're working on to the north side of the valley.

One of Amy and Kaimana's primary responsibilities with the HBWS is to manage the forested watershed area of upper Makaha Valley which not only provides critical habitat for Hawaiian plants and birds, but also captures rainfall and helps replenish Oahu's drinking water supply. In contrast, the lower valley is dominated by California grass (Urochloa mutica), Guinea grass (Megathyrsus maximus), and the nonnative shrub haole koa (Leucaena leucocephala) - all of which ignite easily and carry rapidly moving wildfires.

A wildfire burned over 1,000 acres in Makaha Valley in 2007, sweeping up this side of the valley and towards the upper, forested area of the watershed. Fortunately it was put out before it caused significant damage to homes or native habitat. Several fires have burned closer to the coast since then, but with the dry grassy vegetation provides plenty of fuel for wildfires to spread quickly across large areas.

NONNATIVE GUINEA GRASS, CALIFORNIA GRASS, AND HAOLE KOA CREATE VERY FIRE-PRONE VEGETATION IN LOWER MAKAHA VALLEY.

It is understandable, then, that Amy and Kaimana are concerned with putting in some kind of break to slow or stop future fires from damaging the forest. The subject of fire breaks opens up many questions - where do you place it? how wide? how do you reduce fuel loads within the break? how do you pay for establishing and maintaining the break?

Amy's been thinking about this at least since the 2007 fire and has some great ideas and had some great input from folks at Hawaii's Department of Forestry and Wildlife. As far as placement, the first step is really understanding where wildfires are likely to come from relative to the area that is being protected - in this case the upper valley. In Makaha, most of the fires start in the lower reaches of valley nearer to where people live - most wildfire ignitions in Hawaii are caused by people. The next strategy concerning fire break placement is to try to 'tie' the break into existing features of the landscape that would help to stop or slow wildfire. These can include roads, streams, reservoirs, or exposed, rocky areas - any place with a low chance of burning. Fire breaks take a lot of work, so part of this strategy is to minimize the length of the break.

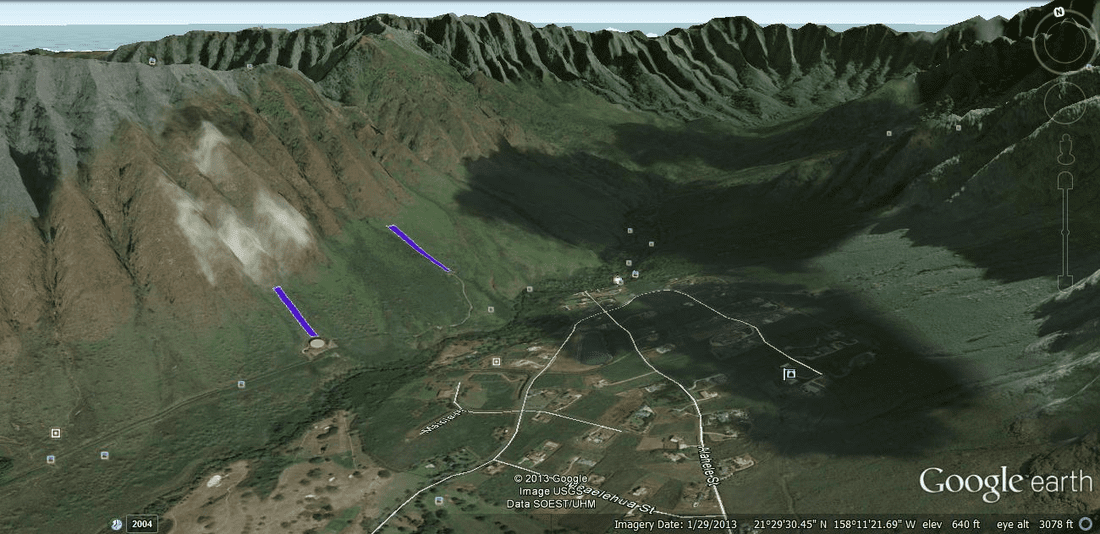

Fortunately, for the breaks on the north side of Makaha, there is an upper access road which provides two sections of the valley slope that are relatively short distances to the cliffs above. Still leaves quite a bit of work - but its a good place to start.

VIEW OF MAKAHA VALLEY LOOKING MAUKA (TOWARDS THE MOUNTAINS). THE FIRE BREAK LOCATIONS ARE SHOWN IN BLUE.

Nothing stops a wildfire as well as fuel break cut wide and cleared straight to bare soil. But this type of break takes an enormous amount of work to establish and maintain. And in some places, especially in the steep mountains of Oahu, completely removing vegetation may lead to erosion and soil loss. An alternative approach is altering the structure of the vegetation to make it less likely to burn.

Amy and Kaimana are just at the initial stages of designing their fire breaks, but their idea is inspired by permaculture, which incorporates economic and food-producing trees into agriculture. The use of trees as fuel breaks is also called a green strip, living fuel break, or shaded fuel break. Trees shade out grasses, reducing fine fuel loads, and slow the spread of fire. Two challenges for the living fuel breaks in Makaha are that they need water and time to establish. Amy and Kaimana have installed little catchment systems to water their seedlings. But until these trees establish a canopy, the grass fuels will still need to be reduced and/or removed. So far, all this is being done by hand and with the help of volunteers.

It is also important to note that a green strip might not stop a wildfire. But even slowing a fire can be a huge help to firefighters. Wildfires rip through grassy vegetation so quickly, that it usually is not possible for firefighters to engage them directly. Having harder-to-burn, woody vegetation in the way of the fire's leading edge may not extinguish the fire, but it may slow it down enough to give responders a fighting chance.

CATCHMENT TO WATER TREE SEEDLINGS IN THE UPPER FIRE BREAK.

Amy sees the permaculture approach as a way of engaging the local community by establishing plants they would value in addition to helping with wildfire. As well as native trees like milo (Thespesia populnea), they are experimenting with non-native trees such as mahogony and lignum vitae - both valuable timber species - and have plans to try food trees like avocado, tamarind, and breadfruit.

Amy and Kaimana's work also illustrates that although wildfire management does require specialist knowledge - such as the experience and equipment for fire suppression - many wildfire prevention measures also require local knowledge of the landscape and community. This knowledge is something most landowners, land managers, and residents already have. Successful wildfire management requires combining specialist and local knowledge and community involvement.

Clay Trauernicht, Extension Fire Specialist

Dept. of Natural Resources and Environmental Management

College of Tropical Agriculture and Human Resources

University of Hawaii at Manoa

VIEW OF THE GATED COMMUNITY IN THE UPPER RESIDENTIAL AREA OF MAKAHA - ALL BUILT IN A HIGH FIRE RISK ZONE. NOTE THE TREES PLANTED ALONG A DRAINAGE TO THE FAR LEFT - POTENTIALLY A GOOD PLACE TO STRENGTHEN FOR A FIRE BREAK TO PROTECT THE UPPER VALLEY.