In "Partner Perspectives" we get to know the diverse people, roles, and views of wildfire management in the Pacific. This month, we feature Paul Higashino, Natural Resource Specialist V, Kaho‘olawe Island Reserve Commission, Department of Land and Natural Resources on dealing with wildfire and restoration in Hawai‘i. (Note: the interview was conducted and edited by Melissa Chimera)

Name: Paul Higashino

Role: Natural Resource Specialist V, Kaho‘olawe Island Reserve Commission

How would you describe your role?

I was hired to start the Hawaiian native species revegetation efforts on Kaho‘olawe in 1996.

Describe your earliest memory of wildfire.

It was 1974 and I had just turned twenty. I was at Hawai‘i Volcanoes National Park (HAVO) working under a graduate student Tissa Herat making collections. I got pulled into the Keanakakoi eruption fire with Jim Jacobi, Rick Warshauer, H. Eddie Smith and others. They needed people to slow and stop the fire. Alien vegetation (Andropogon virginicus and A. glomeratus) was burning and carrying the fire beside native species.

It was 1974 and I had just turned twenty. I was at Hawai‘i Volcanoes National Park (HAVO) working under a graduate student Tissa Herat making collections. I got pulled into the Keanakakoi eruption fire with Jim Jacobi, Rick Warshauer, H. Eddie Smith and others. They needed people to slow and stop the fire. Alien vegetation (Andropogon virginicus and A. glomeratus) was burning and carrying the fire beside native species.

What did you do on that fire?

We were trying to stop the advancing fire using piss pumps and flappers. The fire truck broke down on the escape road and we didn’t have the support of a fire truck.

What was your takeaway from this first fire suppression experience?

Just that they needed help I was there. The next fire was in 1979 at ‘Āinahou. Also, Dr. Cliff Smith had me redo some of the fire transects and plots that Terry Parmen set up after the 1975 Hilina Pali fire.

In your early years, it sounds like research was really integral to fire.

Yes, it was. When I was at HAVO between 1981 - 1988, I took courses including fire and advance fire behavior, ignition specialist, squad boss. After the 1983 eruption of Pu‘u O‘o, fires happened just about every month. Then there was the 1987 uila (lightning) strike fire in the ‘Āinahou area. We would set up transects and vegetation plots to monitor the recovery of the native plants and/or weeds in that area. I also monitored fire plots along the strip road kīpukapulaulu (bird park).

Initially you were working in fire, then in native, intact Hawaiian rain forests in east Maui and elsewhere. Finally, you came to dry, barren Kaho‘olawe in 1996, a stark contrast. Why?

In 1978 I worked for a Navy contractor doing botanical surveys. That is when I had a passion. I fell in love with Kaho‘olawe. Afterwards, I would go out with Protect Kaho‘olawe Ohana (PKO) from 1980 - 1984, growing plants for them in the early 1990s. Then I applied for this job in 1995 and began in 1996.

What was your initial impression from that first visit to Kaho‘olawe in 1978?

It was devastated. The island was so destroyed. But in that barrenness there was also a beauty, too. In reality, the modification of the island started when the Polynesians arrived. They slashed and burned, introducing agriculture. Goats were brought in 1793, then cattle ranching and finally the military’s occupation of the island. All of these combined activities put Kaho‘olawe into its current state.

It's interesting that you describe a devastated place like Kaho‘olawe as beautiful back when you first visited. Why?

To me, the beauty was the beaches. Seeing ‘opihi growing on rocks in a calm bay where you rarely find ‘opihi on the other islands along accessible areas. The colors of the hardpan. It’s a different beauty perhaps.

I’ve been reading about how artists and naturalists sometimes go to devastated places to make art or to restore them. They feel the destruction but also the beauty. For example, Chernobyl is a place where a photographer has been on-site taking pictures of the radiation—the free-floating photons—and finding beauty in a post-nuclear waste site. There can be an appreciation for the aesthetic of a place even when it has been really hard hit.

Yes. In documentaries or photos of Chernobyl, you see the table still set in the house, the toys still on the ground. One thinks of the laughter, the camaraderie, the activities. Although Kaho‘olawe was bombed, there are many places where it’s as though people just got up and left. Pu‘u Moiwi has various workshops where people formed adzes from the rock. It would be like going to someone’s pottery or surfboard workshop, where they just threw out the broken pots or boards. You can hear the chipping of the rocks, imagine the stories of being chased by the shark in the ocean, catching the biggest wave. They are all gone.

Being on Kaho‘olawe sounds like time travel where glimpses of the past—both pre- and post-contact times—are compressed together.

In areas like the hardpan where there is no vegetation—nothing at all—you see a fire pit, or evidence of a dwelling. You think, how difficult was it to set up a house here? Yet, in the past there might have been a hill, and therefore it may have been more protected than just this barren landscape.

What is your relationship to Kaho‘olawe?

It’s a beautiful place to work. We can experiment with what others have tried throughout the world in revegetating barren areas—or other cultures trying to survive, slowing the advancement of sand dunes. For these people it is a matter of life and death.

Tell me about the personal sacrifices of your work.

There has been a lot of sacrifice over the past 24 years; for my family, going to the island for one to two weeks at a time away from my wife and my three boys, spending time away from home. But I also spent a lot of time there with my boys, driving around, working, going to a beach where it’s only us. Our footprints are the only ones on the whole beach. I have many beautiful memories being out there with my family.

What are the unique environmental, political, social opportunities or challenges that Kaho‘olawe presents you as a land manager?

I tell people, I have it easy on Kaho‘olawe. I don’t have animals. I don’t have the public. I chose not to use the words “problems” or “difficulties” or even “challenges.” For me, it is opportunities. When I left The Nature Conservancy after twenty years of working in native ecosystems, I thought, I can bring experience to the table. Back when I was considerably younger, I came to this as a little arrogant. I was cocky, like, I can do anything. Working at Kaho‘olawe threw that all out the window and really humbled me to face reality. It is a completely different animal; the environment, logistics, managing the people. We do have bombs.

What is the hardest ecological question to answer at Kaho‘olawe?

How do you revegetate the hardpan, or basically Costco parking lot where there’s nothing around to give you reference? Driving around O‘ahu and Maui, seeing the weeds in a parking lot gave me ideas. Also, Boone Morrison or Robert Wenkam’s photographs of an ‘ōhi‘a tree or ‘ama‘u fern coming up in a barren a‘a flow. What happened there? In both instances, the seed, spores, moisture gathered. They were able to grow. An experience like trying with great difficulty to pull up fountain grass on Kaho‘olawe affected me—this weed with a 10 inch long root has a little leash in the crack of the ground. Why? It wanted to survive. I thought, I have to find a native that can do this.

And have you found a native species that can do this?

Yes—we have pili grass, a‘ali‘i, ‘āweoweo, ‘ohai.

Tell me about the unique re-vegetation project on the hardpan—the pili grass bails—on Kaho‘olawe.

Tell me about the unique re-vegetation project on the hardpan—the pili grass bails—on Kaho‘olawe.

Over five years, the Plant Materials Center on Moloka‘i grew pili grass from Kaho‘olawe seed, as well as kawelu (Eragrostis variablis), a‘ali‘i and uhaloa. They made the pili grass into bales like hay which we then placed on the hardpan. We threw a palm-full of seeds in them and walked away. Depending on the rainfall, plants sprouted three months or up to two years later. In total, we threw out 8,000 - 9,000 lbs of kāwelu seeds. Early on, phytophthora (water mold) did kill off seedlings. This little kīpuka—or niche in this barren landscape—would gather soil and organic matter while containing moisture. Now, formerly barren areas have some vegetation.

How do native Hawaiian plants survive in a nutrient and water deficient environment?

Instead of digging a hole with a pick and shovel, we used gas power augers, then added organic matter, compost, fertilizers, soil amendments. Our first 60,000 plants’ survival rate was 5%. But after drip irrigation, the survival rate went up to 80-90%. In 1992, we built a half-million gallon water catchment system with three tanks and main lines running out to our planting areas.

What about revegetation where ordnance might be present?

Our project with the Hawai‘i Department of Health is within 120 acres where ordnance has been only surface cleared down to a depth of one to four feet. This means there could be a bomb underground where we plant. Therefore, we weren’t permitted to dig a single hole. Instead, we found little rivulettes (ditches), laid the plants directly onto water-soaked ground, and placed soil compost and rocks on top.

We made rock mounds/circles with wood chips inside, leaving them for two months to accumulate windblown soil and organic matter—then laid plants beneath directly on the ground, adding soil amendments and irrigation. Since 2014, we’ve put in 40,000 seedlings with a survival rate of 80% while moving 150,000 lbs of rock via milk crates and/or buckets. That has been a very successful project.

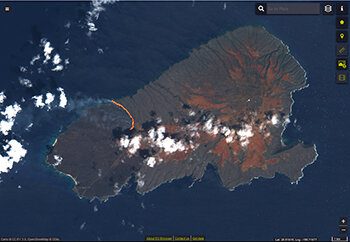

Tell me about the most recent 9,000 acre fire that burned a third of the island. What was the cause?

It is undetermined. The fire started Saturday, February 22, 2020 and lasted about a week. It began on the west coast and burned slowly into the wind towards uncleared areas with ordnance. By Sunday, the winds changed to westerly turning it into a head fire after which it swept north

You couldn’t suppress the fire because of Kaho‘olawe’s ordnance?

On bombing ranges, you don’t fight fires because ordnance could go off. There were reports of flashes going off in the night. Was it a flair up from vegetation? Or was it ordnance burning up? Maui Fire Department and the Department of Land and Natural Resources did fly out regularly during and afterwards to monitor the fire. Towards the end, we directed two Windward Aviation helicopters to put out the fire in a particular area.

What about Kaho‘olawe’s facilities and infrastructure?

Although the fire came close to the basecamp, the solar field, power lines, many of our buildings, none of these burned. However, the fire jumped the road and destroyed one of our main storage facilities. We lost all the planting tools, herbicide, three Polarises [ATVs], two jet skis.

What were the pre-fire planning technologies that protected structures during the fire?

Some solar fields require constant maintenance in keeping the vegetation down. Our solar field is very close to the ground, not on a raised platform. Instead, the builders laid down cement cloth that you roll out, then water it, and it hardens up.

Given that you were in wait-and-see mode, how did the fire eventually go out?

The fire eventually spread to sparsely vegetated buffel grass “islands” (30 - 40 m apart) which were still burning. This type of spotting is a very big problem. Is the fire out? I’d like to think so. But then, remember the Puakō fires on the Big Island in the 1980s where fires popped up from burning roots one to three months later. On Kaho‘olawe, it’s not the well-burned, hotspot areas—it’s the edges that are the concern.

Tell me about the impact of the fire and the rise of alien species.

The many of the alien plants previously brought to revegetate Kaho‘olawe are fire adapted. Fire is part of the life cycle of buffel grass (Cenchrus ciliaris) and mission grass (Pennisetum polystachion) which are already rebounding, gang-busters. It was a little disheartening and depressing. There are a few native Hawaiian species that can tolerate a fire, but not fire adapted. The natives plants themselves (‘uhaloa, ‘ilima, Pannicum fauriei) and the seed bank are either gone or reduced.

What proportion of the restoration work was wiped out by this fire?

Two of our planting areas burned completely, essentially two years of work. We were restoring a 4 to 5-acre wetland along the coast of Kaukapakapa funded by the Natural Resource Conservation Service. The fire swept through the ma‘o (Hawaiian cotton) shrubland. The second is a 2 to 3-acre wetland at Kealialalo where we did a lot of clearing of alien kiawe, most of which burned. I think of all the people that we brought up to plant, like my two older boys and their classes.

It has to be heartbreaking to go to those places with all the memories of your family, your work. They are special ecological areas, niches which are emotionally resonant, unique, and significant.

Yes. I think of other restoration projects—Haleakalā Ranch, Hakalau, ‘Auwahi. These places still have remnants of native species. For example, the little gully or exclosure that people put up years ago to protect a single species. But on Kaho‘olawe, finding natives to put out there was very difficult. The vision statement asks us to revegetate with native biota. With current funding or personnel, we are trying our best, but there will be a lot of alien plants. These species are conserving the soil, slowing erosion.

What is your perspective on the long term consequences of military occupation with respect to land management?

I know it is a sensitive subject. I’d like to think that because of our military and our government, we live the lifestyle to which we are accustomed. In talking with those who lived during WWII, back then people perceived that a threat was still there. Also, I think of other military reservations (Camp Pendleton) where native ecosystems exist because of limited access to the area. For example, I worked at Pohakuloa Training Area (PTA) in 1977 where we found seven or eight supposedly extinct species. We were unlikely to find those plants outside of PTA’s fenceline, because of the animals on the other side.

Do you view this fire as an opportunity or a crisis, or both?

I would look at this as an opportunity, as there is always opportunity in change. For Kaho‘olawe, it’s about maintaining fire breaks around our buildings. How can we re-do things? How can we re-think what we have been doing—from managing people, organizing tools, or even what species do we put in the ground? I’m the eternal optimist trying to get more native vegetation out there—or perhaps limit the spread of alien plants. Perhaps the goal might be to make a sanctuary for certain native species within Maui Nui.

Speaking of Kaho‘olawe as a sanctuary for rare species, what is the status of the kanaloa—the world’s single population of a remnant plant that was once widespread throughout Hawai‘i, on the sea stack off of the island?

The ka palupalu o kanaloa on the sea stack is no longer. We do have four plants in cultivation, two of which have produced considerable native seed this year.

Some say that wildfire may be beneficial to Kaho‘olawe because unexploded ordnance was uncovered and the fires burned invasive vegetation. Might this allow for more native species, and possibly establishing a seabird colony?

Those areas where bombs might have gone off are still officially off-limits to us for restoration. If I had 10,000 lbs of native seed on hand to throw out—or even throw out another type of alien plant—we could make a difference. Conservationists might say, what’s Paul thinking? But maybe there is another lower growing species that doesn’t carry fire—not to replace the buffel grass per se, but to reduce the amount of [highly flammable] grasses in the long run.

What is at the top of your wish list? If you had your $10 million dollar check and/or silver bullet what would you do?

We will be establishing areas of native a‘ali‘i and ma‘o. The purpose is to collect pounds of native seed, stockpile and throw them across the island every few years, thereby adding to the seed bank. The island will burn again, maybe not for another 10 to 20 years. Somehow, we have to change the fuel type—specifically the buffel grass—so that a future fire isn’t so devastating. Buffel grass adds allelopathic chemicals to the soil, encouraging germination of its own seeds, and/or inhibiting other plants.

To your point of converting vegetation from flammable to less flammable, is there a non-native species that might serve this purpose?

I’m still trying to figure that out. It would be great if someone with the technical knowledge and/or financial means for changing the vegetation at scale could help. Do we just continue weed-eating fire breaks because it is cheaper in the long term? Or do we aim for some type of lower growing vegetation? How is it done in densely populated areas? Do we bring out a landscaper and ask how much it would cost? I’m not saying a lawn that you can put a golf ball on—but something that can reduce (not necessarily eliminate) the spread of fire.

Do climate change projections for temperature and precipitation guide any management decisions for Kaho‘olawe?

Our water is pretty low right now—down to the last 10% of a 400,000 gallon tank that should be full. Maybe we do more selective plantings in a little rivulet or ditch, as opposed to mass plantings in the hardpan. We are planting ‘aki‘aki grass (Sporobolus virginicus) at Honokanaia, our main support infrastructure, in anticipation of big surges due to increased sea level. The question is, how do we reduce the flooding potential by planting on the beaches? We have changed the shape of the beach already with the build up of a bigger sand dune.

What are the topics or trends in fire prevention and management that we should be talking about?

The question remains for the Kaho‘olawe and Ma‘alaea, Maui pali fires, why were there areas that didn’t burn? It was the type of fuel. There was less of the main carrier, the flammable grass. Perhaps it is a change in strategy. Do we let it burn every couple of years, or do we wait ten years for a big one? With all that we have—helicopters, drones, radio communication—do we puff up our chests and say, we can put any fire out. Instead, perhaps we direct the chopper to the right area, instead prioritizing zones ahead of time for fire suppression. I think overall, it’s getting everyone to the table with an open mind and thought process.