In "Partner Perspectives" we get to know Po‘okela Hansen, Honolulu Fire Department and Protect Kaho‘olawe ‘Ohana member who recently visited Kaho‘olawe after one-third of the island burned in February. We learn his perspective as both native Hawaiian and an active firefighter, as well as his concerns about covid and why drones can save lives. (The interview was conducted and edited by Melissa Chimera)

Name and Role: Po‘okela Hansen, Honolulu Fire Department and Protect Kaho‘olawe ‘Ohana (PKO) member.

How would you describe your role?

I have been a firefighter with the Honolulu Fire Department for twelve and a half years. I am also a member of the Protect Kaho‘olawe ‘Ohana (PKO) as a kua, access guide. I help organize the access for volunteers in the community, assist the water safety crew, and operate the zodiac which transports volunteers between Maui and Kaho‘olawe. When I first started, I was curious, wondering what is Kaho‘olawe all about? After my first access I was hooked. I then trained to be a kua.

Could you go back to that first trip to Kaho‘olawe and recall what that was like?

Before I became a firefighter I was fortunate to go as a teacher with Kamehameha students. It was absolutely amazing—to see both the good and bad of what man can do. I really felt and appreciated the love for place, people and time. This captivated my heart because it allowed me to self-reflect, to appreciate the things that I have. I came away thinking, what can I do today to make tomorrow better, or leave the place better than the way I found it? Also, living in a city I don’t get the opportunity to see millions of stars at night. Kanaloa has a very interesting way of pulling our deepest feelings and thoughts from you and challenging yourself. Everything we bring—we either walk, swim, or shuttle things over from Maui. The appreciation I have for my culture was one of the greatest takeaways from my first trip.

How is your role with Protect Kaho‘olawe ‘Ohana different from that of a firefighter? Is there ever a conflict between the two?

The roles are similar. As firefighters, we have three priorities. First, it’s life safety for us and others followed by incident stabilization. We want to make sure the situation doesn't get worse—in fact, we'd like it to get better. Lastly, there’s property conservation. The safety of everybody is our responsibility as kua. Everything we do is safety, safety, safety. We have an orientation before you sign up, when you land on Maui, one when you arrive on Kaho‘olawe, and every day thereafter. In this way, both of my roles mesh together. I work with other kua in assigning responsibilities like kitchen duty and incident stabilization projects. Of course, what we do there is aloha ‘āina, malama ‘āina—taking care of the land. As firefighters, we don't want the land to burn. I’ve seen native plants disintegrate. It's very sad.

Were you on the February fire at Kaho‘olawe or were you watching from afar?

I was watching on social media. Friends were sending me pictures. My brother-in-law is an inter island pilot, so he was sending me pictures. That's all we could do. Pray, or pule.

That must have been just a nail-biting time—to have such an intimate relationship with a place that you love intersecting with your profession.

Yes. Four of us went ahead of the fire to safeguard the PKO camp. Maybe that's where the conflict comes into play. In my experience as a firefighter, we have to continually evolve our strategy or tactics. As a PKO member, I thought perhaps there were things we probably could have done. However, from the firefighter’s standpoint it wouldn’t have been safe, especially not knowing about unexploded ordnance. Some of my friends on Maui saw large plumes of smoke, like a mushroom cloud bomb. I think that some bombs probably went off and that's why no active fire fighting could take place.

That’s interesting that you were able to go there ahead of the fire spreading across the island.

We were able to push back some of the brush near the PKO camp. There’s a traditional hale—na maka pili—that's made out of pili glass. If one ember catches, the whole thing could have burned. We sprinkled dish washing soap on to the top of the hale. We tried everything we could.

Were you able to safeguard the camp?

The fire stopped well ahead of the camp. After the fire, we were granted access to go with Halau ‘Ōhi‘a but then covid came and they shut down all travel. Just this last week (in late July) was first time I had been back, four months later.

How was it to be back on Kaho‘olawe after the fire?

THE ALALOA (TRAIL CLEARING) TEAM AND THE HAWAIIAN FLAG LEFT STANDING AFTER THE FEBRUARY FIRE WHICH BURNED 9,000 ACRES (PHOTO: PO`OKELA HANSEN).

It was wonderful, a small group of only ten. But it was also a little bit sad seeing a lot of the work that we had done destroyed. We had a camp with about $10,000 worth of equipment—weed whackers, chainsaws, cooking equipment—all reduced to ashes. As I approached our campsite, I saw that it was completely burned down to ashes except for one thing: in the unburned

area less than a foot away from our tent was a Hawaiian flag. It was the same flag that was carried by one of our dear friends, Kealoha Hoe, who came with us the previous September and who unfortunately passed away. So in a way, he was there doing his part to fight the fire. (Coincidentally, there’s a video with all of us singing in the jam for Mauna Kea “on the barren slopes of Kaho‘olawe” and you can see that flag behind us) There is the opportunity to rebuild the area to make it better.

How has firefighting changed with covid?

It's been a very big challenge. Basic common sense things are now priorities: washing your hands, wearing facial coverings, disinfecting surfaces, tracking who comes in and out of the fire station. Our policies had to change. Community members can’t come in for blood pressure. They have to stay outside. Prior to covid, we were very heavy on community outreach.

Fire stations function like schools in a community?

Exactly. I run the youth program with 14 to 20 year olds who are interested in the firefighting profession. It’s a very popular and successful program where we've actually been placing some of our students into fire departments. We built up a lot of good momentum but haven't been able to have a meeting since February. It’s a little bump in the road, but that's okay. This is just the new normal and we’ve just got to change the way we do business, get creative.

Being that you are medical responders in many instances, are you all suited up now? Do you have enough Personal Protective Equipment (PPE)?

Yes. Our support staff does a really good job of anticipating needs. In the beginning, PPE was flying out fast. N95 masks were in demand by community members. Now we have procedures for acquiring PPE. We wear face coverings (which was a requirement before) thereby reducing risk of transmission. I will say that the fire stations are one of the cleanest places that I know, maybe cleaner than my own home. Every day when we start our shift, we check the truck, check the equipment, and we clean the station. Covid is reinforcing a lot of things that we already did. We take extra care with our equipment by disinfecting the bags if we go to alarms, for example.

Getting out to Kaho‘olawe must have been a relief amidst the coronavirus concerns.

It was. However, this last trip was a pilot program to bring the community even with covid, since the overall goal is continued access to Kaho‘olawe by the community. Until there is a vaccine, it will be very hard to assure the safety of everyone. Everyone wears facial coverings. We sanitize our hands. There is one person as a designated cook and server wearing gloves. We did a great job showing that this can be done.

What is your long-term vision for Kaho‘olawe?

I hope to see it become a thriving place, a wahi pana of ocean and land resources where people can acquire their most basic needs to survive, to live there. We need the land a lot more than it needs us, but it takes that reciprocal relationship of caring for each other. We do a lot of good work, but imagine how much more we could do if people were there for longer. I think the food supply could be established and water might be a challenge but we can be creative. We have a lot of young, smart minds who come to the island with great ideas. They could take the kuleana of Kaho‘olawe and run with it. I want the island to continue to be a sustainability classroom for the keiki, the kupuna, a place where people can go to reflect, to learn, to kokua. There’s a lot of people who want to go who are on a waitlist, but it is hard to get there.

How has this most recent wildfire changed your perspective on fire suppression?

I knew Kaho‘olawe was high risk—so dry, not a lot of water, favorable fire conditions. But it made me realize how insignificant we are in the greater scheme of things. We can do all this good work, building trails, but sometimes the plan is different and we have no control over that. The only thing we have control over is our intentions and how we make each other feel. The fire, covid, the hurricane—we are just tiny in this world. It made me appreciate the time that I have, the people and places that I love. It humbled me a lot.

Paul Higashino (Kaho‘olawe natural resources manager) mentioned that one of his takeaways from the fire was that he and the staff should be maintaining fire breaks. Given that sentiment, do you look at the fire as an opportunity or a crisis?

Definitely an opportunity. After the fire, that was our number one project: clearing about a 5 to 10 ft fire break around our camp. We cleared everything down to the dirt. We cut down a lot of the trees and the brush, cleared out the gutters, so that in the future if the fire does get close we are giving our camp the best chance possible. I’ve also been part of the Kaho‘olawe alaloa (long trail) group for about 10 years. Our goal is to build a trail around the entire island for Makahiki and other cultural ceremonies, thereby connecting with our ancestors by circumnavigating the island.

When I think of cultural rituals around the world, it fundamentally comes back to connecting with our ancestors in whatever form that takes. Given the importance of Kaho‘olawe to Hawaiians, what is your perspective on the long-term consequences of military occupation?

I respect the decisions that were made back then. I was still a kid so it’s not until you actually see the damage to the land that you realize how bad it is. The long-term effects are still there. The land has taken a lot of beatings. Things have a hard time growing. There is a lot of runoff, ordinance all over the place. People gave up their lives.

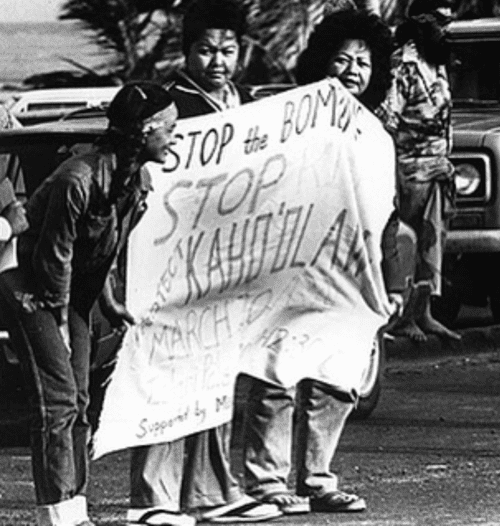

Can you describe the history of Hawaiian resistance and sacrifice at Kaho‘olawe in the 1970s?

The military was using the island to test all different types of weapons—anything and everything that could kill, maim or destroy. A bunch of brave individuals felt that what they were doing was wrong, so they stood up for what they believed in by occupying the island. The protocol was that the military had to temporarily stop the bombing while looking for anyone rumoured to be on the island. These individuals not only sacrificed their lives, but also their careers, their families. They sacrificed a lot.

Did the protestors actually die on the island?

They were lost at sea paddling back to Maui.

So, their efforts opened up a whole new conversation about Kaho‘olawe’s future?

Yes, and because of their sacrifice we have the opportunity to restore this land. Had it not been for their courage, I'm not sure if we would have had this opportunity. We're fortunate to have a lot of the individuals who occupied the island. For example, Uncle Emmett Aluli as a medical doctor may not have been looked upon favorably in his role as an activist back then.

Describe some of the recent changes in firefighting as a profession.

We are using more technology to fight fire and for emergencies. For example, the fire department has a drone program for conducting reconnaissance over fires. This avoids putting our personnel at risk. A drone might cost $2000, but that’s small in comparison to a life. And with helicopter reconnaissance you're not putting people in danger. You’re still getting information that can be used to strategize and to plan during a wildfire.

Do average people recognize that firefighters wear so many hats, like medical responders for example?

About 70-80% of Honolulu Fire Department calls are medical in nature. The remaining 20% could be an animal rescue, a patient assist, car accident or fire. As a result, we’ve had to refocus more towards medical calls, because there are a lot more fire stations than ambulance rigs and hospitals. If we are going to provide emergency services, we should get some of our firefighters up to par and certified as EMTs, so that if someone’s heart stops we can administer CPR. This gives these individuals a better chance of survival. We've been having a lot of fires as well which reinforces that you know we can't just focus on one thing. We’ve got to be very diverse in our training.

Describe some of the diverse firefighters training.

This year our training is focused on water safety, radio communications and chainsaw. In January, I took a fire investigations course at the National Fire Academy which opened up my awareness to different things. On this latest trip to Kaho‘olawe I noticed that in Ahupū area the fire seemed to have spread underground possibly through tree roots, whereas the remaining tree was left standing and mostly unburned.

Do you have any message to the public and average homeowner for how best to prepare for fire?

Being aware of your surroundings is the most important thing. For example, both you and your neighbors need to push back the brush because if yours is well-manicured and your neighbors isn’t then it won’t make a difference. Maybe a lot of adjacent conservation lands don't get as much attention as you think they should, but that’s because they don’t have enough money or people. Take it upon yourself to get involved through the Sierra Club or other organizations to protect your community. Especially in the leeward areas wildfire will spread so fast it goes so fast that before you know it, fire is jumping valleys. Another problem we’ve noticed is the litter, trash, abandoned cars, beds which magnify the intensity of the fire in these brush areas. During the summer, our fire department issues out fire safe messaging to communities. It seems like it’s every other year we have big fires.

The fire research shows that it’s the previous year’s rains followed by drought which determines how bad the fires are going to be, especially given that 98% of all fires in Hawai‘i are human-caused.

It's even more of a challenge for us here in Hawai‘i being isolated, given that the rest of the country has the ability to receive mutual aid from other jurisdictions. We're on our own and we have to really be smart about how we use our resources. As a result, a lot of the fire service people in Hawai‘i are leaps and bounds ahead of other places. Yes, our operations are small, but we are able to navigate with limited resources.

What do you think about prescribed burning?

I think sometimes it’s necessary. I know here on O‘ahu, I've seen some fires get out of hand and then we’re there fighting fire for a week.

It’s true that O‘ahu has not had the greatest track record, but there are places on the mainland that do it well. I'm just wondering if there might ever be a situation where we can revisit prescribed burning as a tool, like if it's too expensive to herbicide, weed whack or even run animals through an area.

I think prescribed burning a better alternative than using chemicals.

Set up with the right conditions, I could see prescribed burning being used as a cost-effective, less expensive option to clear fuel break corridors, especially in alien dominated areas that are maybe protecting native habitat further away.

I believe that anything worth having is worth working for. Persistence is the defining quality between failure and success. If you have to weed whack it every single week, then you’ve got to be persistent. For example, I know Kaho‘olawe has a lot of dedicated individuals that work to protect sacred land including the Protect Kaho‘olawe ‘Ohana, the Kaho‘olawe Island Reserve Commission. All of us have the same goal in mind which is to restore some of the most sacred lands that we have left in our state. The island serves the purpose of bringing people, ideas, values together. We need to perpetuate this. We all may not be in the same profession but we can all work towards a common goal and Kaho‘olawe does that in its magical way by bridging gaps between people.