Understanding the Grass-Fire Cycle can help to better manage grasslands and savannas, reduce the risk of wildland fire, and limit the impacts of re on our communities, watersheds, and native ecosystems.

Tags: Fire Ecology & Effects, Grass-Fire Cycle

Did you know?

-

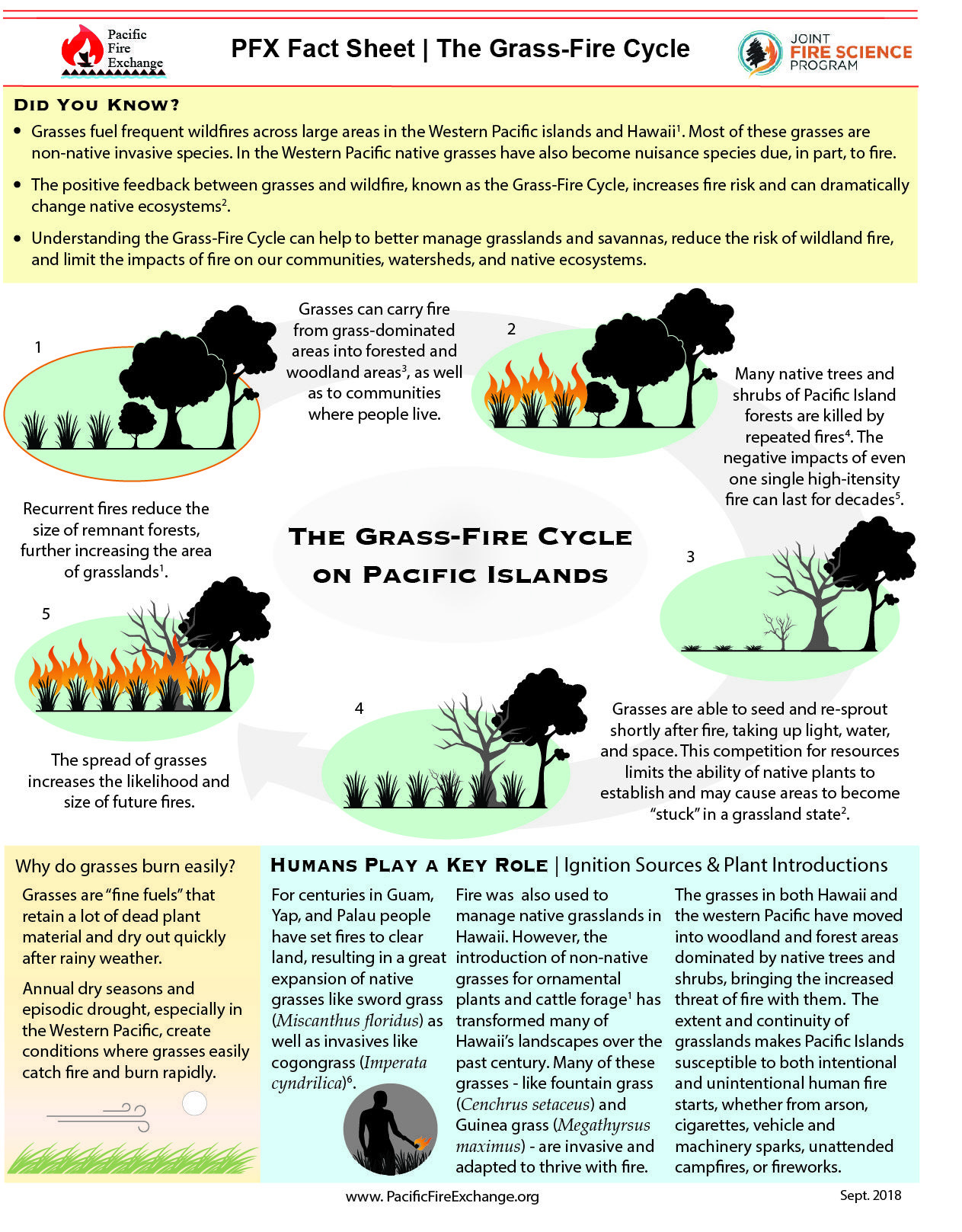

Grasses fuel frequent wildfires across large areas in the Western Pacific islands and Hawaii (1). Most of these grasses are non-native invasive species. In the Western Pacific native grasses have also become nuisance species due, in part, to fire.

-

The positive feedback between grasses and wildfire, known as the Grass-Fire Cycle, increases fire risk and can dramatically change native ecosystems (2).

-

Understanding the Grass-Fire Cycle can help to better manage grasslands and savannas, reduce the risk of wildland fire, and limit the impacts of fire on our communities, watersheds, and native ecosystems.

Why do grasses burn easily?

Grasses are “fine fuels” that retain a lot of dead plant material and dry out quickly after rainy weather. Annual dry seasons and episodic drought, especially in the Western Pacific, create conditions where grasses easily catch fire and burn rapidly.

Humans Play a Key Role

Ignition Sources & Plant Introductions

For centuries in Guam, Yap, and Palau people have set fires to clear land, resulting in a great expansion of native grasses like sword grass (Miscanthus floridus) as well as invasives like cogongrass (Imperata cyndrilica) (6). Fire was also used to manage native grasslands in Hawaii. However, the introduction of non-native grasses for ornamental plants and cattle forage1 has transformed many of Hawaii’s landscapes over the past century. Many of these grasses - like fountain grass (Pennisetum setaceum) and Guinea grass (Megathyrsus maximus) - are invasive and adapted to thrive with fire.

The grasses in both Hawaii and the Western Pacific have moved into woodland and forest areas dominated by native trees and shrubs, bringing the increased threat of fire with them. The extent and continuity of grasslands makes Pacific Islands susceptible to both intentional and unintentional human fire starts, whether from arson, cigarettes, vehicle and machinery sparks, unattended campfires, or fireworks.

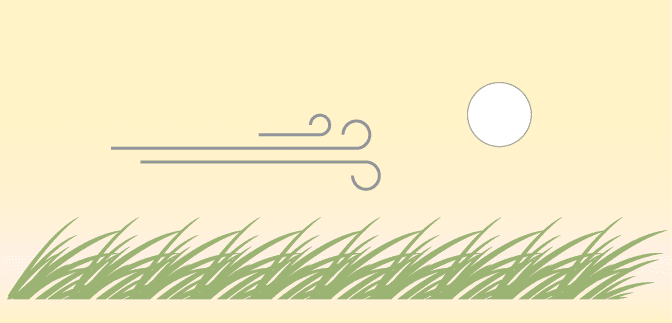

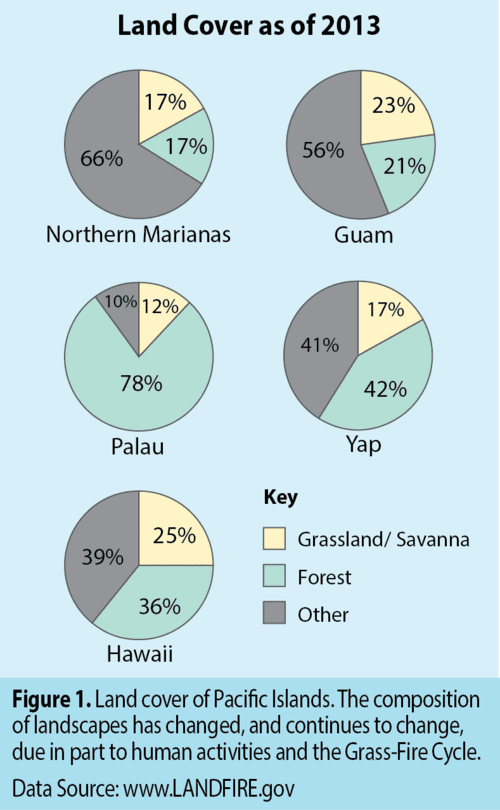

Management Strategies

Grass-dominated landscapes occupy large portions of the US Affiliated Pacific Islands (see Figure 1). Many of these areas were formerly managed for other uses. Land abandonment - letting landscapes go unmanaged - often leads to conversion of those areas to grasslands with increased fire risk. Despite what these grasslands used to be, they are now re-adapted ecosystems because the less fire-tolerant species have been displaced from them. Research indicates that grasses can persist for decades even without fire coming back, and that grasses limit the recovery of native forest without active human intervention (5).

Different land use strategies are key to limiting the grass fire cycle. These strategies include livestock grazing, diversified farming, and forest restoration. The challenge is implementing or reestablishing land uses at large scales over the landscape.

Ecosystem Restoration

Planting native trees and shrubs in re-impacted areas can exclude non-native trees and grasses over time (7). In practice, this is challenging because many grasses and non-native plants grow faster than native plants and outcompete them in the post-fire environment.

In addition to possible weed control, plants in restoration areas need protection from fire (see Traditional Fire Management below) until they can competitively exclude non-native grasses.

Traditional Fire Management

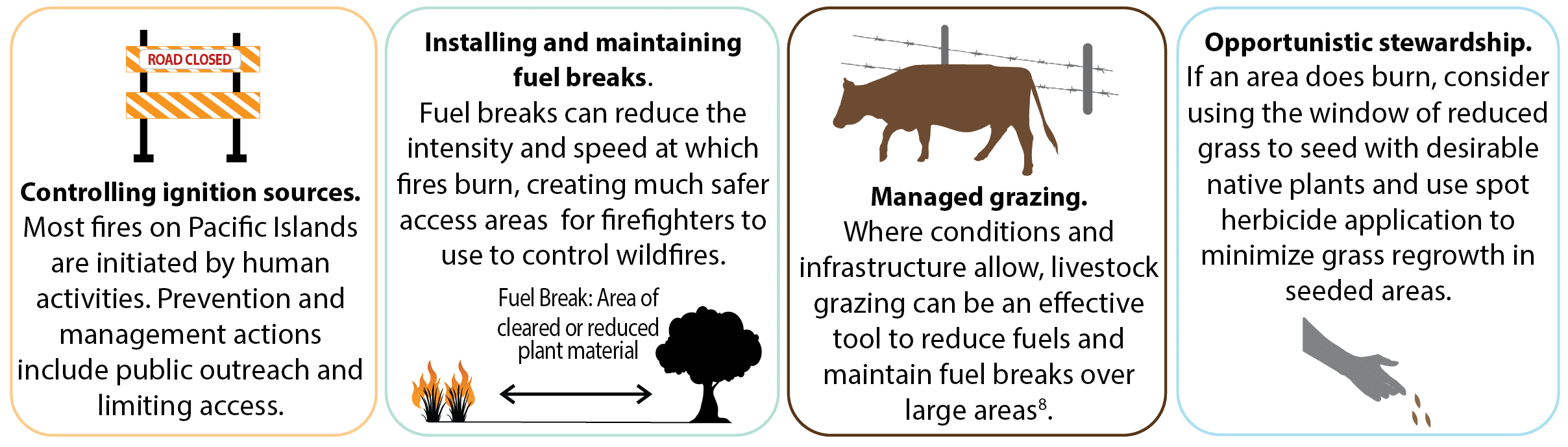

In addition to ecosystem restoration more traditional approaches to fire and fuels management are recommended. These approaches include:

Future Work

Only a few studies have examined the changes in Pacific Islands ecosystems and plant composition following wildfire, and they cannot reflect every landscape affected by fire in the Pacific. For more specific Grass-Fire Cycle management recommendations that fit the different cultures, ecosystems, and landscapes across the Pacific, more knowledge must be gathered, generated, and shared by communities, landowners, land managers, and researchers. If you have management strategies or projects that aim to limit or break the Grass-Fire Cycle that you'd like to share, please contact the Pacific Fire Exchange ([email protected]).

Credits & Collaborators

Content: Carla D’Antonio, Dept. of Ecology, Evolution, and Marine Biology, University of California Santa Barbara; Stephanie Yelenik, Pacific Island Ecosystem Research Center, US Geological Survey; Clay Trauernicht, Dept. of Natural Resources & Environmental Management, College of Tropical Agriculture and Human Resources, University of Hawai‘i at Manoa.

Layout & Design: Melissa Kunz, Hawai‘i Wildfire Management Organization

Vector graphics from www.Vecteezy.com

References

- Trauernicht, C. et al., 2015. The contemporary scale and context of wildfire in Hawai‘i. Pacific Sci. 69:427-444.

- D'Antonio and Vitousek. 1992. Biological invasions by exotic grasses, the grass/fire cycle, and global change. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 23:63–87.

- Ellsworth et al. 2014. Invasive grasses change landscape structure and fire behaviour in Hawaii. Applied Vegetation Science.17: 680-689.

- Ainsworth and Kauman. 2013. Effects of repeated fires on native plant community development at Hawaii Volcanoes National Park. International Journal of Wildland Fire, 22.1044-1054.

- D'Antonio et al. 2017. Ecosystem vs. community recovery 25 years after grass invasions and fire in a subtropical woodland. Journal of Ecology 105:1462–1474.

- Athens and Ward. 2004. Holocene vegetation, savanna origins and human settlement of Guam. Records-Australian Museum. 29:15–30.

- Ellsworth et al. 2015. Restoration impacts on fuels and fire potential in a dryland tropical ecosystem dominated by the invasive grass Megathyrsus maximus. Restoration Ecology. 23:955 - 963.

- Pacific Fire Exchange. 2016. Grazing to Reduce Blazing [Fact Sheet]. http://www.pacicreexchange.org.