O‘ahu

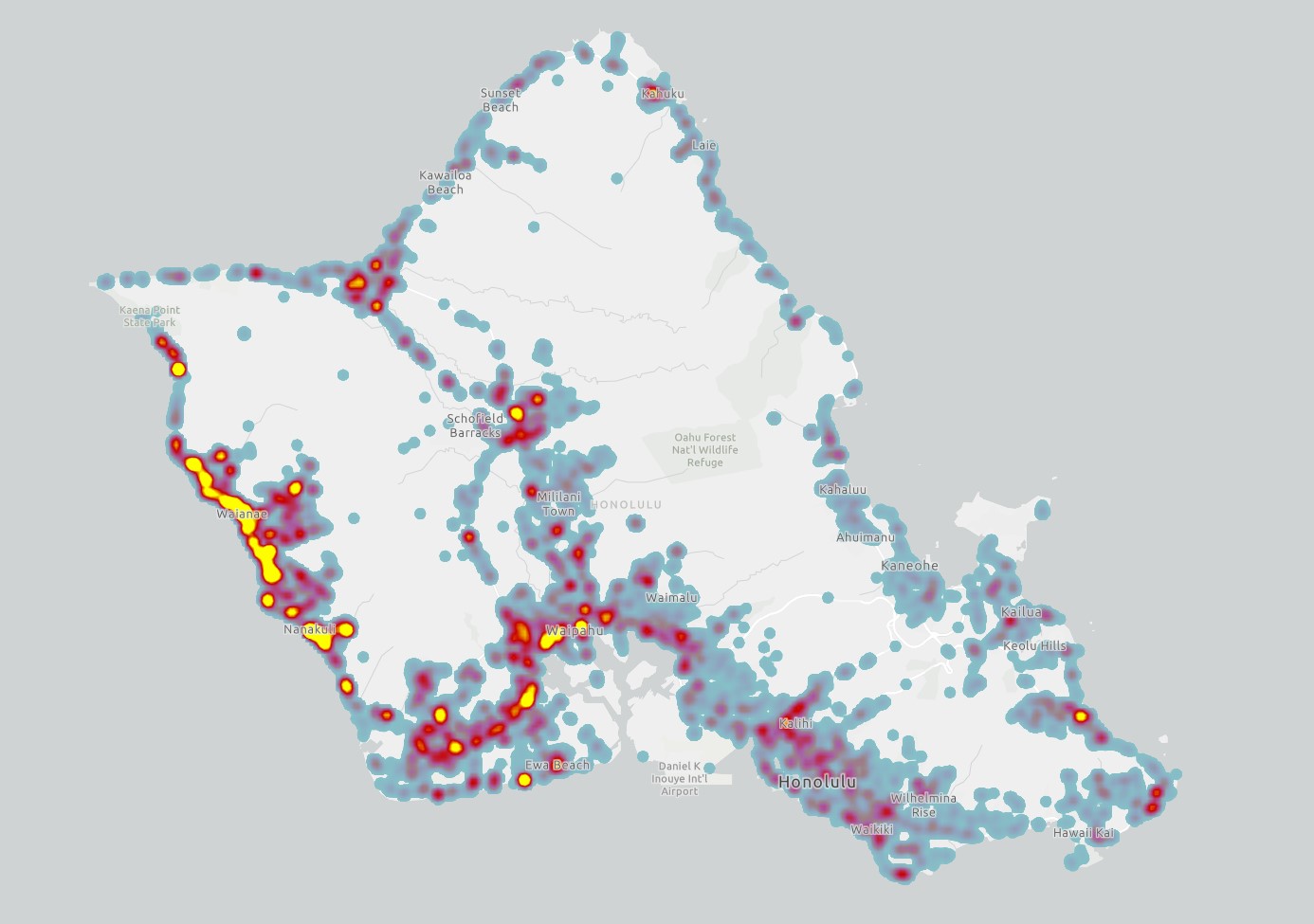

As the most populated island in Hawaiʻi, Oʻahu experiences a significantly higher number of wildfire ignitions than other islands. This elevated ignition rate, coupled with densely populated communities in close proximity to fire-prone shrublands and grasslands, presents a potentially hazardous situation for thousands of residents.

The steep slopes of the Koʻolaupoko and Koʻolauloa regions on the windward side intercept a substantial portion of the moisture from prevailing northeast trade winds, resulting in the distinctive wet windward side and drier lee areas. The most vulnerable areas on the windward side of the island are around Kāneʻohe Bay, where ignitions, winds, and subdivisions bordered by patchy grasslands increase risk, and near drier Kahuku to the north.

Along the leeward south shore from Pearl City to Hawaiʻi Kai is the island's most densely developed region. These tightly packed neighborhoods extend from the coastline into the heads of valleys, often bordering numerous fire-prone shrublands and grasslands, exposing residents to increased wildfire risk. Hawaiʻi Kai, in particular, is exposed to trade winds originating from the north, which wrap around the eastern tip of the island. Furthermore, Hawaiʻi Kai is adjacent to lowland areas dominated by non-native vegetation in grasslands and shrublands, as well as cliffs and ridges that may experience periods of drought.

The central region of Oʻahu stretching from Waipahu to the Haleʻiwa on the North Shore, lies between the Koʻolau mountains to the west and Waiʻanae range to the east. This area contains both well-developed urban areas and the island's most extensive region of current and former agricultural lands. This wildland-urban-interface is at greatest wildfire risk for loss of property, life, and natural resources.

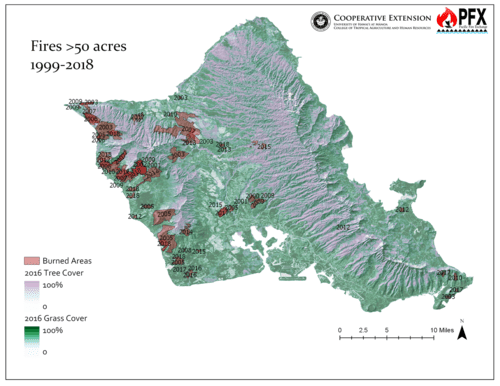

Western Oʻahu, on the lee side of the Waiʻanae mountains, is where the most frequent large fires have occurred. Fires starting in the lowlands near human infrastructure, effectively “erode” the edges of upland forested areas, which become replaced by grasses and increase the risk of fire over time. Unfortunately this intersects with the highest density of threatened and endangered species on Oʻahu. Several notable fires have extinguished populations of various native, endangered species including the 2007 Waialua fire which destroyed a population of the Hawaiʻi state flower, maʻo hau hele, and the 2018 Keaau fire which destroyed one of the largest stands of wiliwili trees.

Recent Resources For Hawai‘i

We measured fuels (live and dead fuel loads, type, height and continuity) and modelled potential wildfire behaviour (flame height and rate of spread) inside and outside of 13 ungulate exclosures, three of which received active ecological restoration (e.g. planting of native shrubs and trees), across a 2,740 mm mean annual rainfall (MAR) gradient on the Island of Hawaii. Differences in fuel characteristics and modelled wildfire behaviour inside versus outside of ungulate exclosures were assessed using linear mixed effects analyses.

- « Previous

- 1

- …

- 24

- 25

- 26